Delivered at the Crossroads Conference, Temple Bar, Dublin, 19 April 1996

WEB VERSION NOTE: The following essay is approximately 13 A4 pages long. If you would like to read, save, or print it out in single page, print-friendly format, click here

I’m pleased that this debate on ‘innovation ’in traditional Irish music is taking place in public and I think it’s appropriate that the venue is here in Temple Bar, where there is such a concentration of new thought in so many fields of Irish Art.

I want to say at the outset that I regard traditional music as an important part of the Irish artistic landscape and this music deserves to be taken as seriously as any other sector. I say this because it has been my experience over many years that our native music and song has generally been regarded as entertainment of a fairly primitive nature.

Underlying the affection of a large section of the public for it, is a preconception – that apart from its entertainment value, traditional music has little of artistic importance to offer. More importantly, its value in terms of addressing the spiritual desert that covers much of the western world today, including Ireland, remains unexplored.

I’d also like to say that opinions I express on this subject are my own and are based on my many years apprenticeship as a listener to musicians and singers whose paths I was fortunate to cross in my life. Much of what I have to say is based on what I have observed and learned from them. They were people of artistic modesty and generosity of spirit, larger-than-life characters who inspired us, taught us and lit up our lives.

Séamus Ennis

Séamus Ennis

They were people whose memory I cherish… Seamus Ennis of Fingal, Ellen Galvin, of Moyasta in Clare, Joe Heaney and Sean O Conaire of Carna and Rosmuc, Tommy Potts of Dublin, John Doherty of Glencolmcille, Martin Rochford, John Kelly and Micho Russell of Clare.

This whole debate is, of course, an old one and traditionally, a private one. I remember the late Joe Heaney expressing strong views about guitar accompaniment of traditional music and singing in 1965 – at the height of the so-called ‘ballad boom’ – and I remember even stronger views from distinguished traditional performers of that time on issues such as the taste and discernment that should be shown by a performer in both tthe choice of material and in performance – in the very way a musician or singer should regard the music that has been handed down by those who have gone before .

Always at the centre of this continuous debate was the principle of care, and of respect – care for the shape and form of music that was a gift from previous generations, a gift of great significance and value, freely and generously given. Respect for that music was also regarded as important – especially in performance where young musicians were present. They often spoke about the effect of a great performance on both musician and listener – how the whole climate of the mind could change in seconds, binding listener and musician in a shared spiritual moment… Music, I once heard said, is the language of passion.

Martin Rochford

Martin Rochford

The musicians and singers I’m talking about demonstrated these qualities in their own approach to music and they had a particular dislike for the business of what I would now call joyriding with traditional music, pushing it around, as one player said on TV, to see what would happen.

This current phase of debate has the misleading theme label of tradition and innovation – which first of all suggests an ideological conflict between traditional musicians who are progressive and those who are backwoodsmen or purists – like myself!

I’ll have something to say later on the use of the word purist… the current banner term of the sleeve-note philosopher/commentator who regards anyone challenging his diet of received commercial wisdom as a primitive… a sort of home-grown hill-billy.

Whatever ideological disagreement there is between musicians, it doesn’t and shouldn’t extend into personal relations and I would feel much closer to some of the innovators whose work I find boring than I would to others whose music I love. So, I’d like to make clear in advance that the issue that concerns me is strictly music… and not personalities. And incidentally Irish Traditional Music isn’t my favourite music and hasn’t been for a long time. Anyway, we’re all in the proverbial public kitchen and therefore we must all share the heat as well as the wine.

STEVE RUANE

STEVE RUANE

This debate – the balance or imbalance between Tradition and Innovation – would have us assume that the new music which we’re told is charting the course of Irish Traditional Music into the next millenium is defined as ensemble music… and that it is solidly rooted in tradition. This is part of my problem with it… because in my opinion it is neither rooted in, nor is it resonant with this tradition.

Where can a place be found here for the spirit of the authentic solo performer from West Cork or South Armagh, in this Hiberno-Jazz scrubbed clean of roots, ritual and balls!

The current phase of this old debate was sparked by a short statement of opinion which I made on The Late Late Show in February of last year, in response to a direct question put to me by Gay Byrne. The entire show that night was devoted to the up-coming television series ‘A River Of Sound.’ It featured most of the main performers as well as extensive interviews with Philip King of Hummingbird Productions, who with Nuala O’Connor produced the series, and Prof. Micheal O Suilleabhain of the University of Limerick who devised, wrote and presented it.

The Late Late that night had an upbeat sense of occasion about it. A few days earlier the President had launched the TV series at an elaborate concert party in Dublin Castle and the Late Late show audience the following Saturday was packed with people associated, in all kinds of ways, with playing, arranging, promoting, recording, broadcasting, packaging Traditional Music and commercial folk music.

The question presenter Gay Byrne asked me, after one of the music performances, was to give an opinion on what I had just heard. I did just that, very briefly, and the entire studio audience went into uproar, shouted me down… led by a roar of BEGRUDGER from one distinguished member of the audience, one who speaks with an assumed authority about an art form, the expression of which lies far beyond the borders of aspiration.

Thinking that maybe I was in a national minority of maybe a half dozen other begrudgers and Mullahs of tradition like myself (that’s how another self-appointed expert described us recently in the Irish Times….Mullahs of tradition!), my phone started to ring at eight the next morning and over the next three weeks I received 168 letters and calls from traditional musicians from all over the country, all, surprisingly, not only in agreement with what I had said but adding their own views and their own emphasis – much of it very strong indeed.

At the time, it seemed to me that the body of Irish traditional performers had an almighty, long-established pain somewhere in their shared spiritual gut and it seems as if the few words I said that night stuck a finger into the wound and out came anger and frustration.

This is something I understand and sympathise with. After all if a man spends thirty years playing the fiddle for his neighbours in east Clare, he will not be impressed by one individual’s personal speculation on the likely development of his music in the next century, delivered as Gospel whether by musician or Mullah.

Leo Rowsome, his daughter Helena

Leo Rowsome, his daughter Helena

and unknown fiddler at Boyle Fleadh

What seems to have made this more galling still for the solo performers who contacted me – quiet, modest people who don’t care for public debate, whose music comes as naturally to them as breathing – was a perceived hidden agenda… that the innovators claiming to chart the course of traditional Irish music – their music – for generations to come, happen to belong to one or two small musical cliques, representing part of the top end of the commercial folk music sector.

The River of Sound series, in my opinion, failed to mention, let alone address, issues which are central to this debate. I’m going to stay with that series because it has brought us to this particular point and because there isn’t time to deal with several other issues of relevance, for example, developments in the playing of my own instrument, the 2-row accordion, which to my mind have had an adverse impact on our music. Perhaps these other issues could be addressed on a future occasion.

A River of Sound was mounted by Philip King and Nuala O’Connor of Hummingbird Productions in co-production with BBC in Ulster and RTÉ. It was devised, written and presented by Prof. Micheal O Suilleabhain of Limerick University.

Finding the resources for a major series like this is a daunting task and it is to Philip King’s credit that for the second time in 4 years he did it. It must be remembered that whatever any of us think about this series at present, its real and lasting use will be its archive value in years to come, despite the absence of the great majority of mature traditional performers of today.

Major co-productions, however, always come with strings attached, which in this case boil down to delivering a mass audience for what is perceived by TV companies to be music of minority interest. In practise, that meant studding the series with ‘big names’, mainly in the commercial music business, irrespective, unfortunately, of whether or not they had anything of substance to contribute – which in my view they clearly had not!

However, as we the license payers north and south, pay all the bills at the end of the day, the foundation principles of Public Service Broadcasting Broadcasting should be observed. The relevant principle here is that of impartiality in the treatment of controvertial issues; the public is entitled to a balanced presentation of both sides of any and every argument.

SEÁN O RIADA (1931-71)

SEÁN O RIADA (1931-71)

Unfortunately this principle was totally ignored by presenter, producer and director alike, who turned out a series of illustrated lectures more appropriate to a class of music undergraduates in University College Cork than to the core audience of nearly 200,000 viewers of traditional music programmes, which RTÉ has cultivated for thirty years. This audience includes practically all traditional performers – a very large mumber indeed, as well as a great number of good listeners and regular, long-time followers of the music.

Now its one thing to present an imbalanced view of this subject which is dear to the hearts of a great many people; it’s quite another to railroad people in the public eye and the pop music business who know little or nothing about this music into speaking up for CHANGE and DEVELOPMENT, when they clearly illustrate ignorance as to what it is that requires change. After all, what person depending on being loved by the public in one way or another, would speak up against change, when presented with leading questions on TV? Then, having gerrymandered this support for change, they went one further – no voice of dissent whatsoever was allowed and in the case of one maverick who departed the set questions and required answers, myself, the editorial hatchet was used on every last word of dissent. When you think of it, its quite a feat to engage two national Public Service Broadcasting organisations in the promotion of one individual’s controvertial ‘vision’ of this art form. It has to be said, in this regard, that the corporate view of this music held by both organisations, though in different degrees – that it is culturally and technically dubious – probably blinded them to the possibility of serious controversy on such a lightweight subject.

The great traditional music innovators of the last 90 years were also deemed by the producer & presenter not to have existed, apart from unidentified short clips and photographs of some of them, used with ruthless expediency as tags of authenticity: Patrick J.Tuohy, Michael Coleman, James Morrisson, Lad O’Beirne, Ellen Galvin, Patrick Kelly, John Doherty, Frank Cassidy, Seamus Ennis, Patrick O’Keefe, Geordie Hanna, Joe Cooley, Micho Russell, Noel Hill, Iarla O Lionaird.

The main innovators working with contemporary ensemble playing also seem to have been written out of the picture: Peadar O Riada, John Beag O Flaithearta, Bill Whelan, The Chieftains, De Danann and many others.

TOM ROWSOME

TOM ROWSOME

The response I got to the Late Late show gave me heart, because the calls and letters represented a cross-section of serious musicians and singers in this country… people whom I have known for years, whose music is widely respected: Mat Molly, Liam O’Flynn, Seamus Tansey, Noel Hill, Neillidh Mulligan, Paul Brock, Iarla O Lionaird… as well as people who have been quietly playing and singing in their own communities for most of their lives.

What really struck me about the tone and content of these letters and phone calls was their frustration, anger and upset. They expressed various degrees of sadness at changes that are taking place in the performance and interpretation of traditional music today, they expressed anger at what they saw as the selling of these changes to impressionable young musicians, they expressed frustration at the media – especially the electronic media, for slavishly promoting what they (those who contacted me) regard as trendy, spurious and shallow …while at the same time demonstrating a rooted ignorance and intolerance of the wonder and beauty of the music that has been given to us. Manipulation of the media in this field by vested interests was suggested over and over.

One in particular, a musician who had achieved distinction as a solo performer in the late fifties and who is still highly regarded today put it this way : ‘Mac Mahon,’ he said, ‘I’m afraid we’ve been doing it wrong all along!’

That was over a year ago and in the course of my work and travels around the country since then, my eyes have been opened to the distance that has opened up, countrywide, between the main body of traditional performers whose music and song give us unique reflections of the spirit and character of this country and the smaller group of performers who regard this music as a convenient mode of joyriding to the glitzy heights of commercial popularity and success. This is not to say that those involved in the kind of innovation that is most likely to get them there are without love for the music they use as a crutch on that road. They are not. The problem… it seems to many… is not that they love their music less but that they love their careers more.

I think there is one basic question that must be asked – what is music for, what is its value, what can it do for us? Is it an aural carpet, a sort of ear chocolate to soothe our nerves in pubs, traffic jams or shopping centres?

Or, is it a gift to humanity of such proportions that words can do little justice to it? Is it to be reduced, drained of the veiled voices of Ireland, electronically scrubbed clean, packaged and presented as a commercial commodity whose value is measured in record sales, TV Tam Ratings? And in the case of public performance, is its true potential the generation of unthinking roars of conditioned applause?

What on the other hand is happening when a performance sends that shiver up the spine, brings a tear to the eye, when it sharpens and quickens both spirit and emotions to the point where the individual lonely heart is at one with what Tommy Potts called the eternal harmonies?

JOHNNY DORAN

JOHNNY DORAN

If this then is the true power and purpose of music …to bring about a sublime change in the climate of the individual mind by uniting our most tender and sensitive feelings in an orientation towards the supernatural… and I believe it is… what then is the use, the value of Irish Traditional Music in particular?

Is it right that it should be structurally mangled, speeded up out of all proportion, layered and sweetened with carpets of accompaniment, beaten into multi-cultural rythmic patterns, ‘improved’, developed or damaged, depending on where you’re coming from… so as to make it as digestible as possible to an international record-buying, concert-going public?

It seems to me that for those who have ears to hear, this music of ours possesses the power of magic: it can put us in touch with ourselves in ways no other Irish art form can do. It can touch the pulse of ancestral memory, allowing us to redefine our dreams of what it is to be Irish. It can bring the lonely famine landscape to life, it can soothe the trauma and trouble of existence, it is possessed of the veiled eroticism of tenderness. It can adorn a moment of joy, it can sharpen a moment of sorrow. It is a gift of nature, dispensed with the abandon of wild flowers.

I am not aware of what is perceived to be wrong with it and I can say without fear of contradiction that I have sat, talked, drank and listened to all the great players and singers of the last 30 years and I have yet to hear one of them express a desire for the kind of development we’re told is the prescribed path for us now to follow.

In my opinion, that is the path to nowhere – the dreary rattling of universal bones on a desert highway without soul, without hope. If there is an iota of Ireland there, an iota even of human warmth, then I’m a spaceman !

The late Breandan Breatnach defined Traditional Irish music as essentially the art of solo performance – a gift – to which the musician or singer devotes an apprenticship of learning, especially to the great songs and song airs of Ireland. It involves a search for the local footprints of those who have gone before… and it involves a care of not trampling on them when found. It involves a search for the music and songs of one’s own place, and if that is not successful, a search for the music to which the individual musical spirit can resonate.

It means having a mind-set to one’s gift that is devoid of aggression, of narrow personal ambition, of political preconception. It involves an innocence, a humility in being the bearer of a gift that can infuse musician and listener with a shaft of universal joy. It involves an awareness of the natural, internal rhythm of a piece as distinct from its speed, it involves attention to the smallest detail of a tune or a song and most importantly it involves care and discernment when deciding to add one’s own embellishment to a piece of music that has its own local integrity and has stood the test of time.

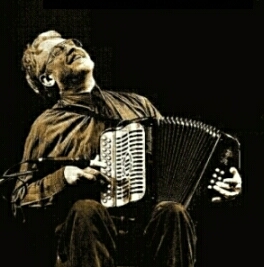

JOE COOLEY

JOE COOLEY

It also implies a maturity of judgement… an independent ear… an ability to question popular approaches to structure, accompaniment, ornamentation and other received ideas. It also requires a practical language of criticism. In this regard we have to think about the opinion makers in this field and consider how they make their judgements and exercise their influence.

I have looked at this process with a number of colleagues in music over a number of years and we have noticed a general unity of opinion and of purpose among those who bring this music to the public… concert promoters, broadcasters, record producers, publicity agents, managers, roadies, groupies and so on. Feeding off each others’ ideas and judgements on what is a most important sector of Irish Arts – their expertise is usually based on a diet of public house philosophy, social gossip, the wisdom of record sleeve notes, the requirements of the entertainment and folk music markets.

While self-appointed experts indulge in exchanges of mutually beneficial services, favours and ego-massage, the skilled solo performer who has borne the heat of the day is expected to keep his opinions to himself, as those before him had to do in the ’sixties, or at least confine them to the kitchen corner. If he, or she, should dare to step out of line, a quiet policy of exclusion and marginalisation slouches into place. If, in that instance, a musician or singer is dependant on music for a living, then its time to go into a quiet room and write a new social intercourse script.

The contemporary folk-musack boat must not be rocked….

On the basis, then of BREANDAN BREATNACH’s definition of Irish Trad. Music, which is the one I care to use, I wouldn’t regard the bulk of contemporary ensemble treatment of this music either as traditional or interesting. I find much of it boring, repetitive, mechanical… cavorting and jostling its way along the entertainment superhighway in search of a comfortable stall in the market-place.

I have no great problem with the market-place, though I have great memories of the respect shown for the Arts in former East Germany, or by the GLC in London before Thatcher, for example, but I do think arrangers and composers in this particular sector should be prepared to stand on their own creative feet.

I also would have no problem with them thinking this music wasn’t suitable or even good enough for the commercial folk-music market. Neither have I any problem with new music… quite the opposite, I’m all for it… I just don’t think it’s ethical to use the name and fame of Irish Traditional Music as a crutch or as a substitute for what cannot otherwise be achieved in the popular music market.

After all, Bill Whelan and Michael Flatley did it with the original work of Riverdance, and with no prescription that theirs was the correct road for all of us to follow into the next millenium.

Another problem I have with ensemble treatment of traditional music is that it leaves little space for individual expression – and no amount of the kind of feigned ecstasy, either the beatific countenance or the hinge at the butt of the neck as we saw in ‘River of Sound’ performances can fool a poor Clare fiddler into reading pretence as passion, shadow as substance. I can speak from some experience on the dangers of being involved in public music brawls… because I hold the record of having been sacked out of four Ceili bands, not altogether for perceived ideological impurity but rather for preferring the dancer’s embrace of a west Clare farmer’s daughter to the tumult of the Tulla Ceili Band at full throttle!

It was at my desk in RTÉ that The Bothy Band first started, but I left after the hype of the first couple of public performances, because the music was regarded as a vehicle, again for the same joyriding to fame … and again at even fuller throttle than the Tulla Ceili Band!

It seems to me there are two kinds of innovation in this field: what I would call internal and external innovation… internal… as demonstrated by the masters of this century from Patsy Tuohy through to Micho Russell. This was the innovation of individual genius… for which our music, in my opinion, provides full scope… innovation that will stand the test of time. The other kind seems to me to mainly a process of rotovation for handy musical tricks and compositional ‘glickery’ and its place in the next century could very well be the river-bed of spent fads and fashions.

Turlogh McSweeney

Turlogh McSweeney

But whatever hype the commercial quartermasters, the gurus, the opinion makers, the commentator camp- followers can muster, it won’t fool Paddy Cronin in Killarney one little bit.

It’s interesting and significant that the art of sean-nos singing, which is, after all, at the heart of this tradition, hasn’t as yet appeared in this whole picture. It seems to have been granted a dispensation from the merchandisers’ commercial game-plan …who as yet haven’t found a way of demonstrating its useability in the market-place. It has been largely ignored, even by the general tribe of musicians. It has yet to be brought in from the cold.

The finest sean-nos singers in this country have no place in the machine which boasts of having created a delicate balance between their tradition and the developers’ innovation. No amount of platitudinous rambling from Dolores Riordan, Van Morrisson or other luminaries of the pop-music world will convince Micheal O Ceannabhain in Carna that his art has a place in the shade, not to mind the sun.

This age-old tradition may yet be the target of the trend-setters, the demi-gods who barter and trade among themselves. Perhaps its the last field ripe for open-cast mining by the musical explorers, who ultimately might even market their wares in new territories of the Far East, that is of course, after explorers of like mind have done the appropriate ground-work in undermining the cultural habitats there, grinding out finer brands of fodder for the commercial cannon …

The signs are already appearing here, for example in the hysterical use of the sean-nos singing tradition as a peg on which to hang displays of public exhibitionism which would be more appropriate to an evangelical prayer meeting in Kentucky than a warm kitchen in Carna.

It’s frightening to contemplate the diminution of diversity in so many small cultures today. The fragmented European psyche isn’t content with the rape of the natural resources of our planet and the resultant loss of animal and plant species diversity. Now we’re targeting the ancient cultural habitats as well, including our own. We’re engaging in this in the belief that no one will contest the selling of everything and that we can rush headlong forward without standing long enough in one place to consider the cultural territory we’ve come from, to leave our footprint there for our children.

Have we not considered that the great minds, including scientists, look to the past in search of answers – and not into the future? Have we not considered the question: ‘Who will teach my grandson if my son doesn’t understand?’ It seems to me that the policy-makers in the field of so-called developement of Irish Traditional Music are patronising in the extreme in their estimation of youth.

Young people today are capable of understanding what we call The Pure Drop, and I would even suggest the marketeers are out of step with national and world trends in their crusade of dragging the youth into the shattered vision of the post-modern techno-music world. After all, if you parachute an African harp-player or a Chinese pop-singer into a Chieftains recording session, you’ll increase the novelty value and sell more units of your product, but you will have engaged in the work of cultural enslavement.

Young people today are capable of understanding what we call The Pure Drop, and I would even suggest the marketeers are out of step with national and world trends in their crusade of dragging the youth into the shattered vision of the post-modern techno-music world. After all, if you parachute an African harp-player or a Chinese pop-singer into a Chieftains recording session, you’ll increase the novelty value and sell more units of your product, but you will have engaged in the work of cultural enslavement.

At the end of this road there will then come a break in the long continuum of vision and we’ll have arrived at a point where the imagination can no longer interrogate the music… where it can’t even speak to it.

Nobody should misinterpret this as opposition to change or development. I’m suggesting no such constipation of the imagination, no objection to putting electric light into a historic building, provided you don’t tunnel cables through foundations, stained glass and ceiling cornices. What I am saying is this: before anyone sits down to carry out a programme of structural or cosmetic improvement on a piece of music or a song that carries the footprint of generations, that person should have the integrity to let his or her life press down into that rich soil of tradition, down through the layers of loam of the Irish experience, and it is only in honourable interaction with that soil, and only out of the depths of that personal experience, can true innovation be created.

This was part of the achievement of the late Tommy Potts of Dublin. He was one of the great innovators, but to define his art in terms of the innovation he brought to a small part of his repertoire is to misunderstand the main message on his music, which was the expression of an almost unbearable mix of emotions and passion. It was rooted in the old piping tradition, nurtured by extremes of grappling with the trials of existence, and grown out of an artistry that was marked by extremes of taste, discernment and tenderness. Of all the musicians and singers I’ve ever met, his was the only music that could skewer its way into the inner soul of the listener and burn his footprint into it forever.

Using an aspect of this man’s art in support of the main thesis of ‘A River of Sound’ is, for me, personally, an act of artistic expediency and cruelty which I found deeply upsetting. I met him in Clare when I was eight, I knew him and his music intimately until his death on March 19th 1988, and I can find not as much as a ripple of resonance between his innovations and those featured on A River of Sound.

This is how Potts played the common march-air ‘Billy Byrne of Ballymanus’ ….a tune from many an afternoon field of dancing competitions, spilt ice-cream, screaming babies and out-of-tune pipe bands. It’s a tune so hackneyed that I’ve never heard it played by any solo performer or group.

Here is how Potts redeemed, redefined and adorned a tune so forelorn, so buried in bad associations that nobody would ever think of playing it. This is a poor recording that gives only a hint, and a vague hint at that, of his greatness. Even though it captured only an echo of his unique voice – he shunned recording and publicity and was a highly nervous man – it nevertheless sets a headline in internal innovation that is characterised by an exquisite sense of taste and discernment, an imagination…and a tenderness beyond words.

So where do we go from here? We have only to look around the few acres of Temple Bar, starting here with this wonderful music centre, to realise that Ireland has at last got up off her knees. Here is a public home for the Arts, where the wonders of modern architecture and engineering provide space for many of the best creative minds. When you think of the fate planned for Temple Bar – a wasteland sitting on top of an underground bus-depot, planned by the same breed of social innovator that destroyed Dublin’s light-rail system – we can say that as a nation we’re no longer living in the hinterland of the oppressor.

Can you name this piper?

Can you name this piper?

I see the resurgence of popular Irish Folk Music as a part of the social fabric today, used or rather underused mainly as light entertainment for tourist and native alike. If we agree that it is an important mountain in the Irish Arts landscape, it requires the same sensitivity and care as brave people devoted to the great mountain of Mullaghmore. We mustn’t reduce our musical heritage to a level compatible with tourist taste or commercial music-traffic. It provides ample scope for developement in the hands of the good solo performer, and equal scope for the inspired arranger. The fact that this country has produced singers and musicians of quality and in numbers out of all proportion to its size, tells us that the infrastructure is in place, willing and fit for challenge.

Let us look under the surface here to see where the real liberals and the real conservatives stand. Let’s take down the FOR SALE sign now, because if you start a business, you’ll soon have to decide who to feed – the hungry, or the business. Let us stop trading in the commodities of cheap paint, tactics and shape-shifting. Let us be modest and caring in the presence of music that carries the race memories of our people, music that sustained them when they had lost everything else. And remember that the people who gave us back so much of what had been lost – our own travelling community – are the very people who face the bulldozer today, and maybe the shotgun tomorrow.

Let us gaze forever forward through the lens of the powerful and majestic past and let us imagine how bleak, how barren the future Irish landscape would be without our traditional music.

Tony Mac Mahon

19 April 96

~

Beautiful Tony, and so true. You sir are a true Irish Chieftain! I am looking forward to the much talked about live collaboration cd with the maestro Steve Cooney. The two of you are such kindred spirits… Your hearts and minds are in the right place.

Read this article for the first time and I must say, it reads like a breath of fresh air today (Jan 13, 2015). I love experimentation in music but when so many are simply studying and reproducing the same big ‘innovative’ sounds and movements without actual creativity themselves, their form of Irish music becomes, ironically, quite bland, the irony lying in the perceived push to ‘innovate’ and ‘joyride’, as Tony mentioned back in 96, from the more traditionally rooted sound, which funny enough finds itself quite in vogue among listeners yearning for ‘organic’, or pure drop, perfor!mances and recordings.

Tony McMahon is keeping the Old Time Irish Music alive. And I agree with him about what has happened to the culture. The music/ dance/ song that have empowered the Irish were like “natural springs” or “wells” that everyone shared and had access to. Now all of those good things have been mutated, undermined, abandoned, and face extinction. The “natural springs” that sustained us and were available to everyone have been taken and turned into things that the average person cannot make for himself like Gatorade, Coke, Pepsi, Mountain Dew, Red Bull, and Perrier bottled water. In fact, the few “wells” that are still available have been ruined due to “fracking.” The simplified music of the Irish had allowed more people to play traditional musical instruments. Playing simplified acoustic music develops the mind and body in many amazing ways which provides advantages. Old Time Musicians/ Dancers/ Singers developed their whole brain and therefore have greater intelligence. The old tunes are sacred/powerful and provide a spiritual connection. Like the Eastern Spiritual Masters, the ego must be quiet/small to connect with our Higher Power/ Ancestors and everyone who participates. For an Old Time musician, the tune is more important than the musician/ singer. The repetition of the simple tune puts everyone involved into a transcendental state of mind. Modern Irish musicians have gone in a different direction. They feel like they are improving the music and giving it a “fresher sound.” “High energy,” excessive use of ornamentation, improvisation to the point of making the original tune unrecognizable, and being like rock stars is the behavior of modern Irish Musicians/ singers/ Dancers. Modern Musicians/ listeners are unable to feel the power of the Old time Irish music. People who are used to caffeinated or sugary drinks are unable to appreciate real “spring water” directly from the “spring.” Without the spiritual benefits, community, or connection to nature, Old Time music seems too simple and boring for “modern” ears. Most Irish musicians I know, who have been trained in the old ways, have succumbed to the pressure to “Modernize.” It is the equivalent to fracking. My generation has aggrandized their egos and mistaken form for content. The advantage of Old Time music it that it is simple enough so that it could allow a lot more people to drink from the ‘natural spring.” And everyone participated. Old Time Irish music is designed to be more user friendly.

Suimiul ar fad

Great and thought provoking read…..much of which I find myself intrinsically in very strong, if untutored, agreement with…..